Article originally published on Horasis.

On March 18, 2021, Horasis held its second digital Extraordinary Meeting, under the theme Rebuilding Trust. Thanks to the incredible work of Dr. Frank-Jürgen Richter, founder and chairman of Horasis, 1100 of the most senior members of the Visions Community – including several heads of governments and key ministers – offered the opportunity to shape the world’s agenda.

I was honored to be able to join an incredible panel, chaired by Metin Guvener with fellow-panelists such as Fahim Naim, Morgan Parnis, and Gary Shapiro, to discuss a vital theme for today’s societies: trustworthy and responsible leadership.

Many nations have noted reduced trust in the ability of political leaders to address the challenges crucial to our daily lives and our future. Cynicism about political leaders is running high, particularly when new pressures arising from globalization are making the involvement of government more important than ever. So how do we install trustworthy and responsible leaders with the inspiration and power to crack the issues that our nations need to solve?

I am pleased to share my contribution to the panel as well as the full session in the video below.

Metin: What is your personal experience and vision of leadership within the transforming world of families, business, politics, and communities locally and internationally?

Manuela: I have spent the past 20 years mostly in financial services, banking, media, and wealth management in Milan, London, and Zurich. Today I’m a consultant to the private and public sector on narratives and strategies around macroeconomic trends, social change, and digital transformation.

I’d like to briefly look back at previous generations. In the aftermath of the Second World War, my grandfather saw his country, Italy, transformed from an agriculture-based economy seriously affected by the world wars, into one of the most advanced and industrialized nations in the world, a leading G7 country. He went from losing two of his baby sisters to the Spanish flu to being able to thoroughly vaccinate his two daughters from birth. From his father’s horses to owning two good cars.

That generation had a very important skill. They had learnt to adapt to any life circumstance, they adapted to change, they trusted competence and institutions, they also had no option. Instead, what we see today at organizations or governments, or among citizens, is often a lack of trust and resistance to change. Experts measure this attitude in AQ, adaptability quotient, and our current generations are not scoring very high.

One reason for this, especially in recent years, can be found in the way information is shared, communicated, and consumed.

During the financial crisis of 2007-2008, I was working in London, the heart of the European crisis at the time.

The financial crisis didn’t merely have disastrous economic consequences, it also negatively impacted the public’s trust in the financial world, in corporations, and in governments, tarnishing their reputation and, as many believe, leading to the strong winds of populism we’ve seen in the past few years.

What went wrong? And what is still going wrong in today’s crisis?

The ability that was most tragically and dramatically lacking during the 2008 crisis – and is still somewhat lacking – was the ability to communicate specifically of industry and governments; to communicate the nature of the problem, what was at stake in terms of risks, and thus why, in America alone, it was necessary to spend $700 billion of taxpayers’ money to solve the problem.

In the light of digital transformation, current information and communication models must be adapted to meet the growing needs of a public – citizens, professionals, politicians, and academia – that has access to ever-increasing amounts of information, and often of fake news, but regularly little clarity and perspective on numerous issues.

In my view, trustworthy and responsible leadership is tied to strategic communication, and is vital for industry and governments. Not only does it have to convey goals, intentions and strategies to stakeholders and society, but it also needs to educate the general public.

Responsible leaders are unbiased thought-leaders to the extent possible on certain topics and must work to reduce fake news and speculation: governments and the industry have a moral duty to provide context and clarity by working together and keeping communication channels open with all stakeholders, including the media and influencers, to create mutual trust.

In the next 10 years, our democracies and the world at large have plenty at stake. It is a decade in which we will set and achieve crucial goals.

A new and strong model of responsible leadership, along with talent and excellence, will help to deal with the most urgent issues, in order to generate new waves of more sustainable and fair growth, capitalizing on essential emotional intelligence and people’s adaptability.

Metin: Mentorship has an important role in everybody’s life, and I know it is particularly close to your heart – can you please elaborate on how it has featured in your life both as mentee and mentor?

Manuela: Mentorship taught me both who I wanted to be and who I absolutely did not want to become. I had both examples of successful, emphatic mentors who were great leaders with a high EQ, and examples of arrogance. As a mentor myself, I have tried to use honesty and transparency as a baseline to show empathy, to tailor my awareness and understanding of situations based on how my mentee was experiencing them.

Mentorship has transformed me in the sense that it helped to see clearly what type of leaders are de facto able to have a positive impact on people, on society, and on our democracies, and those that were extremely damaging. In this sense, it has shaped my understanding of the bigger picture and the importance of what we call “soft skills”, which are the skills that are at the foundation of our societies, our governments, businesses, and that will get us through the next decade.

The popular press focuses on charisma as the mark of leadership, but history is full of charismatic leaders who attracted lots of followers and then led them in manipulative ways.

Metin: Books played a deep and foundational role in your early life as a reader and for some of you, in later life as a writer – what book would you like to share with us today?

Manuela: As a writer myself, I get incredible inspiration from what I read. I have two recommendations, on very different themes.

- “Quiet, the power of introverts”

By Susan Cain. The book raises awareness on how modern Western culture misunderstands and undervalues the traits and capabilities of introverted people, leading to “a colossal waste of talent, energy and happiness”.

In Western cultures, extroversion dominates and introversion is viewed as inferior. The book outlines the advantages and disadvantages of each temperament, citing research in biology, psychology, neuroscience, and evolution to demonstrate that introversion is common and normal, noting that many of humankind’s most creative individuals and distinguished leaders were introverts. Cain urges changes at the workplace, in schools, and in parenting.

- “The Entrepreneurial State: debunking public vs. private sector myths”

By Mariana Mazzucato, Professor of Economics of Innovation & Public Value at UCL. The book talks about the role of governments as drivers of excellence and innovation and describes the role of the public sector as a “top-choice investor” in the history of technological change. There is a plethora of examples of such, often in the US: just think about the favorable setting in which Apple itself was born and has become the colossus we know today.

In Italy, an important example in this sense is the Center for Convergent Technologies of Genoa, created by the Ministry of Finance 25 years ago. A great, high-class research center that has attracted and continues to attract foreigners and Italians, including returning expats.

Today, a comparable example may be the Human Technopole of Milan, the new Italian research institute for life sciences, created by the Italian government in synergy with the private sector, with the aim to become a leading European center of research, attracting national and international talent.

Metin: Having worked with a vast array of clients who have benefited from your strategic advice, vision, value, and voice, can you please explain your driving value proposition to organizations who want to transform their leadership in a trustworthy and responsible manner?

Manuela: I tailor business strategies and narratives at the intersection of macroeconomic trends, social change, and digital transformation, raising awareness and engagement for organizations, governments, and societies on their impact.

My key impact on organizations is helping them build trust as social capital. The social, economic, and environmental challenges of this decade require new approaches to leadership and responsibility. I support them in framing this need, creating the narrative and engagement, and supporting the latter with ad hoc strategies.

Some argue that those in authority positions within an organizational pyramid are the leaders of the organization, and that all that is needed to lead is for the followers to respect the authority of the position. This conception worked in the past, but works less and less in today’s organizations. We are seeing the decline of authority and the rise of trust as an organizing principle. To be effective today, strategic leaders need to combine trust with expertise and emotional quotient.

The definition of trust provided by the OECD Guidelines is “a person’s belief that another person or institution will act consistently with their expectations of positive behavior”. Trust matters for the well-being of people and the country where they live: there is strong evidence on its role in supporting social and economic relations. Trust between individuals and trust in institutions determine economic growth, social cohesion, and well-being. These are crucial components for policy reforms and the sustainability of political systems as well as industry.

Metin: What do you think is a characteristic that great leaders share, and conversely, a habit to avoid so you don’t become a leader who is not expressing full potential?

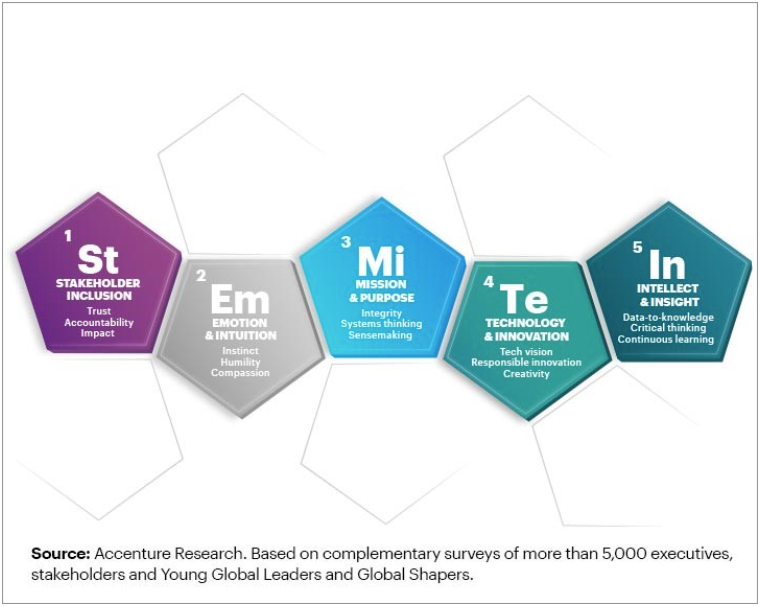

Great leaders leverage emotion and intuition, showing compassion, humbleness, and openness. They listen and empower, promoting common goals by inspiring a shared vision of sustainable prosperity. Moreover, they make digitalization and innovation truly happen, they innovate responsibly through emerging technology, they capitalize on expertise, intellect, and insight, and they are the first ones to embrace continuous learning and knowledge exchange.

A habit to avoid? I’ll quote Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic and pick the most dangerous: toxic charisma.

In times of multimedia politics, leadership is commonly downgraded to just another form of entertainment, and charisma seems a must to keep the audience engaged. However, the short-term benefits of charisma are often neutralized by its long-term consequences.

- Charisma dilutes judgment: There are only three ways to influence others: force, reason, or charm. Force and reason are rational, charm is not. Charm is based on emotional manipulation and, as such, it has the ability to trump any rational assessment and bias our views.

- Charisma is addictive and research proves that it fosters collective narcissism. Especially in the era of social media.

Experts recommend upgrading to a more rational and uncontaminated leadership model by:

1. Selecting leaders using scientifically validated assessment tools, instead of relying on “chemistry” or intuition. For example, narcissists tend to perform well in interviews, and confidence display is often mistaken for competence.

2. Fine-tuning politicians’ media exposure and airtime, which often make charismatic candidates look more competent than they actually are. This has nothing to do with limiting freedom of speech, but rather with tweaking and fact-checking content to provide factual and educational narratives.

3. Finding the hidden talent, avoiding the charisma trap. There is a universal management paradox whereby the people most likely to climb the organizational ladder do so because (rather than in spite) of character traits that impair their performance as leaders. This has been causing a considerable amount of damage at different levels and in all environments, we simply cannot afford it any longer.

Manuela Andaloro

(info@smartbizhub.com)