Article by Manuela Andaloro , with the contribution of Laura Prina Cerai, Senior Investment Advisor, Altrafin AG, and Vega Ibanez, former Senior Project manager, Julius Baer. Published in Focus ON’s cover story, 18th December 2018, download original article in Italian here.

The financial services industry is at a turning point – it has to reinvent itself or it will be reinvented by other players.

Increasingly start-ups and IT firms are attracting a wide variety of new clients interested in specifically tailored services, making it daily more challenging for the entire financial sector to compete and remain engaged.

If we look at access to financial data for example; within the space of just a few years we have gone from making deposits and transactions at bank counters and from phone calls to our client advisors to discuss investments and market trends, to home banking, mobile banking, online trading, AI investment platforms, and a wide variety of valid offers via different applications accessible from our smartphones.

It seems that the industry is changing dramatically directly in response to the demands of customers, who want flexible, new, digital and easily accessible financial service products.

Those who fail to adapt are lagging behind, especially players, banks and institutions who don’t understand the new needs that the ongoing revolution has brought to light. We are witnessing a crucial time of change and it’s only just beginning.

But what led to such an acceleration and to the current financial revolution?

To understand the present we need to go back to the financial crisis of 2007, which we also discussed in a recent post on financial crisis and economies.

How the FinTech world was born

During the last financial crisis of 2007-2008, plummeting share prices, bankruptcies, mergers and restructuring resulted in millions of job losses and triggered the beginning of a fundamental change in the banking sector. Regulators became determined to prevent the actions of one or a conglomerate of a few large investment banks (too big to fail) from hitting the economy and the public purse so hard (hence avoiding further possible bail-outs relying on taxpayers' money). Regulation in the sector has multiplied exponentially and has catalysed most of the direct investments of banks in the last decade at the clear expense of the budget in innovation and improvement of services.

The emergence of new small banks in addition to the big investment banks coincides with a new approach to the services offered: the emergence of the so-called FinTech - new digital technologies in the financial sector - application-based technology that automates most banking processes and offers easy online access and self-service platforms to customers. Today, entire banks are built around a mobile application.

The FinTech industry is seen by traditional banks as an opportunity to participate in the development of the financial sector without the need to invest in in-house development. With thousands of job losses in the banking IT sector in the last decade and the priority given to adapting to regulatory pressure and strengthening budgets, FinTech has developed mainly through outsourcing, driven by the demand of customers disillusioned with and dissatisfied by traditional banks, who were seeking a greater choice of digital services.

This perfect storm led to the rapid growth of FinTech, attracting third-party investments and making it a major player in the banking industry with a customer base that includes some of the world's largest companies. One example is US investment bank JP Morgan Chase, which spent $9.5 billion on IT in 2016. Of the total expenditure, approximately $6.5 billion was spent to support existing IT, while the remaining $3 billion went to new development initiatives, of which $600 million in FinTech.

The incumbent banks have to cope with a crisis of the traditional models of bank and respond to the needs of an increasingly digital consumer, developing more personalised offers and focusing on an omni-channel structure at the expense of the concepts of proximity and territory.

Start-ups and companies that were first to invest in FinTech have therefore gained a wealth of skills and business models that constitute the future of personal finance. And so the traditional banks have begun to opt for a path of collaboration with these newcomers via supporting hubs, financing partnerships or direct acquisitions.

According to Price Waterhouse Coopers' 2017 figures (PWC source study), venture capital investments in the FinTech sector reached a total of $22 billion in 2016. The geographical composition of the capital raised shows that most investment has been concentrated in America and Asia. In Europe, although London has historically been and continues to be the European capital of FinTech, investments in 2016 fell by 34%, mainly due to the uncertainty surrounding Brexit. The slowdown in FinTech investment in the City is offset by the emergence of new ecosystems in Germany, France, Scandinavia and Israel.

Although Italy is currently excluded from the main roles in the FinTech scenario, with no start-ups in the world top 100 indicated by KPMG, it invested a total of 33.6 million euros in 2016, up 77% on 2015 (source startup Italia). Most of the start-ups and investments in FinTech in Italy are concentrated in the mature sectors of asset management, retail banking (traditional payment transactions), insurance and peer-to-peer lending (P2P - i.e. direct private loans, without bank intermediation). Keeping up with the times of change, universities now offer FinTech courses in partnership with local start-ups.

The age of challenger-banks

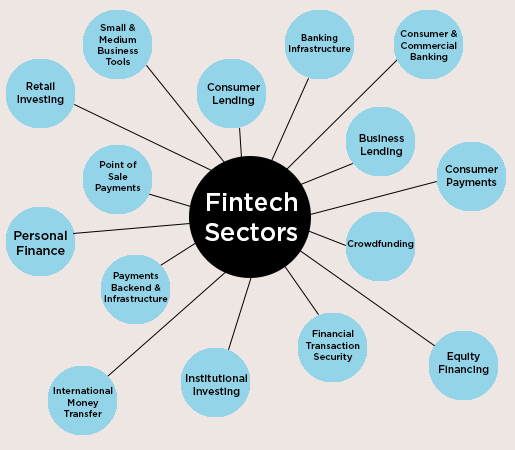

In response to the unstoppable wave of consumer demand, Fintech players are adapting daily to provide all kinds of solutions for private and business customers, globally. Numerous banks and institutions no longer position themselves as "primarily online” and are now "only online".

From deposits and credit lines to payments, consumer and business loans, IMT, institutional investing, personal finance, the new generation of Fintech players is now working more and more strategically with artificial intelligence to digest and analyse large amounts of transactions and behavioural data, to gain a deep understanding of customer needs and match growing expectations.

Payexpo 2018, London. Panel with Chloe Templeton, Megan Caywood, Manuela Andaloro, moderated by Angela Yore

An interesting case is the steady success of the English "Starling Bank". Recently I was invited to talk about my experience in finance at a major event on payments and Fintech in London. One of the speakers on stage with me was Megan Caywood, Chief Platform Officer of Starling Bank (soon to join Barclays as Head of Customer Experience), she used an interesting definition to the describe the bank she helped create: "the digital, mobile-only challenger bank". A bank that has at least a couple of elements that break with tradition: it’s a challenger bank, so a fully digitalised institution with a very light cost structure, and it’s led by a woman, CEO Anne Boden.

Brexit may be changing the financial geography of Europe, but, with best practices like those listed above, at the moment London remains a point of reference for innovation.

The other SPHERE OF “new finance”

2019 will definitely bring further use of automated technologies, further post-GDPR data protection policies, and increasingly strong content control and demands from an increasingly digital workforce and clientele.

We have so far analysed part of the "new finance", and of the response to consumer demands brought by the FinTech world.

There is another very interesting growing reality that has been competing for attention with the FinTech world and similar organisations operating in the world of crypto and blockchain technologies for some years now. The world of sustainable investing.

The so called “new finance” landscape seems increasingly polarised, driven by the forces shaping Fintech on the one hand, and by the need for sustainability on the other.

While the FinTech world comes from an evolution of consumer needs, regardless of age and school of thought, and from the response to post-credit crunch regulatory changes, the other sphere of new finance clearly seems to come from strong demands and needs of younger generations and women.

The millennials - and looking at figures, also increasingly women, no matter which generation they belong to, have been asking loudly for sustainable responsible investments for several years now.

Millennials, most of whom have grown up in the digital age, are - unlike their "baby-boomer" parents - more attentive and more exposed to the evils of the world, and more inclined to use investment strategies to remedy them.

Research shows that “boomers” see sustainability and investment as two separate universes, while millennials struggle to understand how to separate the two.

This generational change already seems to be visible in universities and many business schools report that demand for ESG (environmental, social and governance) investment courses is increasing and they are often overcrowded or overbooked.

"In the nineties, letters of application to Stanford with references to the willingness “to alleviate poverty” in the world were seen as "soft", reports Matt Bannick of the Omidyar Network, a company for impact investments, but today over half of the applications to Stanford Graduate School of Business mention the Institute's commitment to social development goals”.

Bill Gates, Melinda Gates, Warren Buffet

The ultra-rich paved the way. In 2015, a group of millennials, some of whom belonging to the Ford, Rockefeller and Simmons families, launched "The ImPact", a network which aims to create "measurable social benefit" through its investments. Positioned as a generational response to the "Giving Pledge" initiative jointly launched in 2010 by Bill Gates and Warren Buffett, supported by over 125 signatures, each with an average wealth of $700m. Since then, there have been countless similar initiatives, and “Generation SRI” was born.

It's not just the millionaires who are succeeding in this context. It’s a well-known fact that the generation of millennials is less wealthy than that of their parents, yet the older “millennials”, who are almost forty and close to peak-earning, have clear demands and preferences. Over the next two decades, the boomers will pass on their fortunes, worth trillions of dollars - the largest transfer of wealth ever recorded - leaving the millennials quickly in control of about $24trn (Deloitte estimates). Very few people will enjoy the sumptuous pensions of their parents and it is estimated that they will be very determined about how their reduced pensions will have to be invested.

The millennials have experienced the financial crisis, so they are naturally suspicious of traditional institutions. Some people call them presumptuous, because they seem to want to change the world. But is this really presumption or is it perhaps necessity?

In a survey, the American company Morgan Stanley estimated that 75% of the millennials interviewed think that their sustainable investments will affect climate change, in contradiction with 58% of the entire population.

Millennials are also more likely to check the packaging of their purchases for example, and to choose sustainable products, and like all children, they try to influence their parents.

Technology, AI, robo-advisors and the likes, will amplify this force of new finance thanks to increased accessibility. As discussed in a previous post, players that will manage to engage with their audiences successfully will leave the competition at the starting blocks.

Technology leaves no room for impostors. Information on the positive or negative impact of any company will be more and more transparent and available to a growing clientele. Players who are not genuine in their approach to sustainability will find it difficult to hide among what’s on offer, unmasked by algorithms.

Re-writing the basics for a BETTER future

In truth, almost every investment has a social or environmental component. Technology will allow us to create more targeted offers for customers, aligning products, funds, ETFs and derivatives, with sustainable objectives, such as the 17 UN SDGs, the social development goals of the United Nations, and will help measure the impact of our work and our investments, and to ensure increased transparency.

The recipient, customer, consumer has shaped and created the offer. We now own the elements for a better future, brought on by accessible high-level information, slow but steady cultural change and improved awareness of the need for equality, and by a generation that is keen on sustainable approaches towards the way we pursue our businesses daily.

If properly leveraged, technology will enhance information, culture and understanding on the one hand and, on the other, the wise positioning of dynamics, market performance, trends, and the impact that each of us can have on their own future and on the future of our society.

M.

(As published in Focus ON’s cover story, article by Manuela Andaloro for Focus ON, 18th December 2018, download article in Italian here)