Article by Manuela Andaloro , published in Focus ON’s cover story, February 2019, download original article in Italian here.

The single currency has come a long way from the initial dream in which many did not believe. From the first discussions in 1960 on an economic and monetary union, to date, the currency of 340 million Europeans, used by another 175 million people in the world. Its success? It is about combining national identities with global ethos and customs.

One of the skills I have learnt working for twenty years for various companies and in three different countries (ed. Italy, United Kingdom, Switzerland), is being able to read people, finding the key to establishing human relationships based on understanding, trust, empathy: from team members and employees, to bosses, customers, various stakeholders with whom in the last two decades I have dealt and, often, from whom I had the pleasure of learning something.

When dealing with diversity, there are three fundamental aspects one must immediately consider, beyond language and working skills, cultural aspects, or similar experience:

A realistic awareness of one’s value, and the impact it has on others, on business and on society.

Understanding the importance of constantly switching from looking at the big picture to paying the attention to details.

Turning a fixed mindset into a growth mindset while staying humble – an essential skill.

This is what I call emotional competence: integrated skills that are not bound to cultures, nationalities, business ranks, age, generations, education and training. I am talking about skills that can be learnt every day, that make the difference, in my opinion, between those who bring in value, from those who subtract value in the medium and long term: I am thinking of human relationships, businesses, and companies.

Whether we are talking about the latest strategic business plan, a political initiative, the merger of two institutions, or the interpretation of financial statements, the emotional competence of the involved stakeholders is directly proportional to the success that they will achieve in the medium and long term.

Emotional competence and European single currency.

Twenty years ago a new currency was born, it was the single currency of what would be later known as the eurozone: the euro.

It did not exist yet in the form of coins and notes we all know today, which were introduced a few years later, in 2002. In that year, the united currency became tangible for millions of Europeans and the old German marks, French francs, Italian liras, Spanish pesetas, and all the ancient variegated currencies of Europe became History.

Mario Draghi, President of the European Central Bank, once compared the euro to a hornet – a “mystery of nature” that should not be able to fly, but somehow, it does.

Draghi used this metaphor during the tumultuous Greek debt crisis in 2012 when many wondered if the end of the euro was close.

Two decades after its birth, the euro flies high. Member States have grown from 11 to 19, and the size of the European economy has risen by 72%, to 11.2 trillion euros, second only to that of the United States, turning the positioning of the European Union into a global force that should not be underestimated.

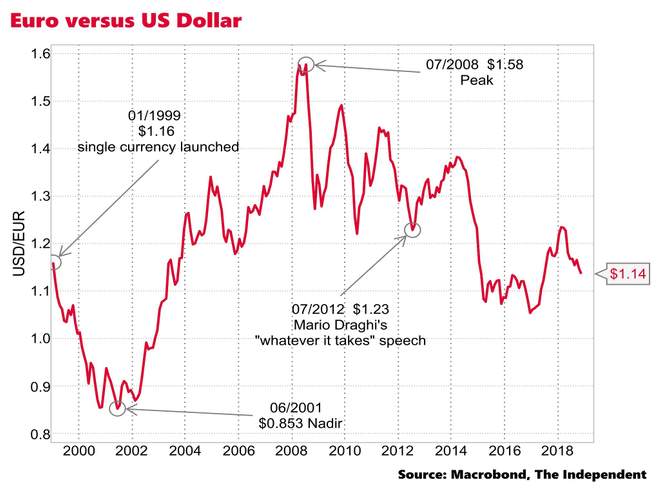

The last two decades have often been turbulent ones for the single currency, from an initial exchange rate against the dollar of $ 1.16, the euro slipped to a nadir of only $ 0.853 in 2001, during the “dot-com bubble” that caused clamorous slips to digital investors of that time. From that moment on, it was a bull market until reaching a peak of $ 1.58 in 2008, just before the financial crisis.

This was the period when rappers like Jay-Z and models like Gisele Bündchen insisted to be paid in euros instead of dollars.

The euro maintained a favourable exchange rate against the dollar during the financial crisis, but a long decline began, once again, in 2014 due to fears related to the eurozone’s rupture.

A key factor was the traditionally interventionist behaviour that the European Central Bank adopted at that time, aimed at supporting economic activities in the areas affected by the recession – an intervention that normally suppresses the relative value of currencies.

Today the euro is stable at around $ 1.14, a position similar to that of twenty years ago.

But how successful was the single currency?

If we look at the annual Eurobarometer survey, the answer is, surprisingly, very successful, given the political and economic turmoil of recent years.

Faced with the question “has the euro been positive or negative for your country?”, on average, the citizens of the analysed European countries have answered positively in 64% of the cases. The same survey in 2002 resulted in only 51% of the population being satisfied with the single currency. The same research in 2018 concludes that in some countries of the block, three-quarters of the population has confirmed that the euro was “a good thing”.

But there are other parameters to take into account, and the great majority of them paints a positive picture.

The single currency is used today by around 340 million people in 19 countries. The euro is today a global reserve currency, stocked by central banks and multilateral institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The Eurozone inflation has been kept under control, remaining on average at 1.7% in the last twenty years, just below the 2% policy imposed by the European Central Bank.

Yet, some economists are not convinced that the euro has been a success, due to the fact that since 2000 the GDP per capita in the eurozone has had a lower yield than expected (purchasing power being the same), growing by 15%, less than the US (19%) and the United Kingdom (20%).

A relative sub-yield.

Yet, this event has significantly less importance than the fact that the single currency has come out unscathed after the serious existential crisis experienced from 2010 to 2015, when the imminent crumbling of the eurozone was feared, at a time when countries like Greece, Italy, Ireland and Portugal ended up under the paralysing pressure of the bond market.

The disaster was avoided thanks to an intentionally vague promise of Mario Draghi, in July 2012, that “we will do whatever it takes” to keep the united market together.

Some regard this episode as evidence that the creation of the single currency was a mistake, that binding economies with different levels of productivity and local institutions, along with a common currency with a single interest rate, would be a doomed project and would create financial, economic and social tensions.

“The euro’s main achievement is still being here, and it’s very likely that it’s here to stay”, writes Constantine Fraser, a European policy analyst at TS Lombard, and he adds “This slightly mad project of a supranational currency union with wildly different economies within it has lasted 20 years and has brought these economies and countries closer together”.

In many cases, older Europeans do not feel European “enough”, but the generational change and the advent of the new generations, grown up in an international environment favourable to integration, will promote the European Union. The eurozone must go on, because if it stopped, it would fall. There is a political will to make sure it continues to grow, but it is still uncertain how quickly and with what incremental changes.

Ten years after recovering from the financial crisis, political instability is now the biggest and most unpredictable threat to the eurozone. The toughest challenge for the European Central Bank during its third decade will be to secure the healthy survival of the union, threatened by the tumultuous background of a significant populist pressure rather than the stress of the financial markets.

Going back to the skills mentioned at the beginning and the much needed emotional competence, let us look at the big picture.

For several generations, the world has been governed by what we now call the “global liberal order”. Bombastic words, whose real meaning is that all men share some basic experiences, values and interests, and that no group of men is inherently superior to another. Cooperation is therefore more favourable than conflict. All men should work together to protect their common values and advance their common interests. The best way to promote such cooperation is to facilitate the circulation of ideas, goods, money and people across the globe.

Although the global liberal order sometimes poses difficulties and problems, it has proved its superiority over all other alternatives. The liberal world of the 21st century is more prosperous, healthy and peaceful than ever in human history. For the first time in history, hunger kills fewer people than obesity, scourges kill fewer people than old age, and violence claims fewer victims than accidents.

We have not died when we were 6 months old thanks to the medicines discovered by foreign scientists in foreign lands. At the age of 11, we have not been erased by a nuclear war, thanks to agreements made by foreign leaders at the poles of the planet, agreements that the new leaders of America and Russia have recently questioned and the expected outcome within 6 months does not look positive.

We should ask those who express their will to return to the golden pre-liberal or even colonial ages, to mention in which year exactly mankind was in better shape than in the 21st century. Was it in 1918? Or 1700? Or in the Middle Ages?

And yet, people all over the world seem to have lost their faith in our liberal order.

Nationalist and religious opinions that favour one group over the other are popular again. Governments seem to increasingly restrict the flow of ideas, goods, money and people. Walls are created, both physical, mental and in the virtual space. Immigration does not persuade, fees and duties increase.

What kind of global order can replace the current one? So far, there seem to be only sketchy and untested solutions at a national level – think of the disastrous example of Brexit –, aimed at promoting the interests of a particular country. But nobody seems to envision how the world, together, should work. Leaving imperialism and global conquests for the history books and science fiction films, what solutions do we have and will leave to our children for the generations to come?

There are real severe threats at the gates of our civilisation. They grow on a global scale, they care little of national borders, and they can only be resolved through global cooperation: nuclear wars, climate change, artificial intelligence and associated technological risks.

However, this is not yet our destiny, we still have a choice. We are still in time to propose a realistic global agenda, beyond commercial agreements. We have the choice to choose, to promote or to reject the leaders – in business, in society, in politics, among our acquaintances – that demonstrate not to have qualities such as understanding the big picture, empathy, humility, that are not aware of the impact of their actions on those who have less means to understand the reality, or worse, who understand and exploit it for their own purposes.

Let us remember the skills of those who, at any level, in any sector, bring in value and have the intrinsic qualities of true leaders: emotional competence.

New identities and solutions are formed in times of crisis. The euro has shown it, so has history.

Manuela Andaloro

(info@smartbizhub.com)

As published in Focus ON’s cover story, February 2019, download original article in Italian here.